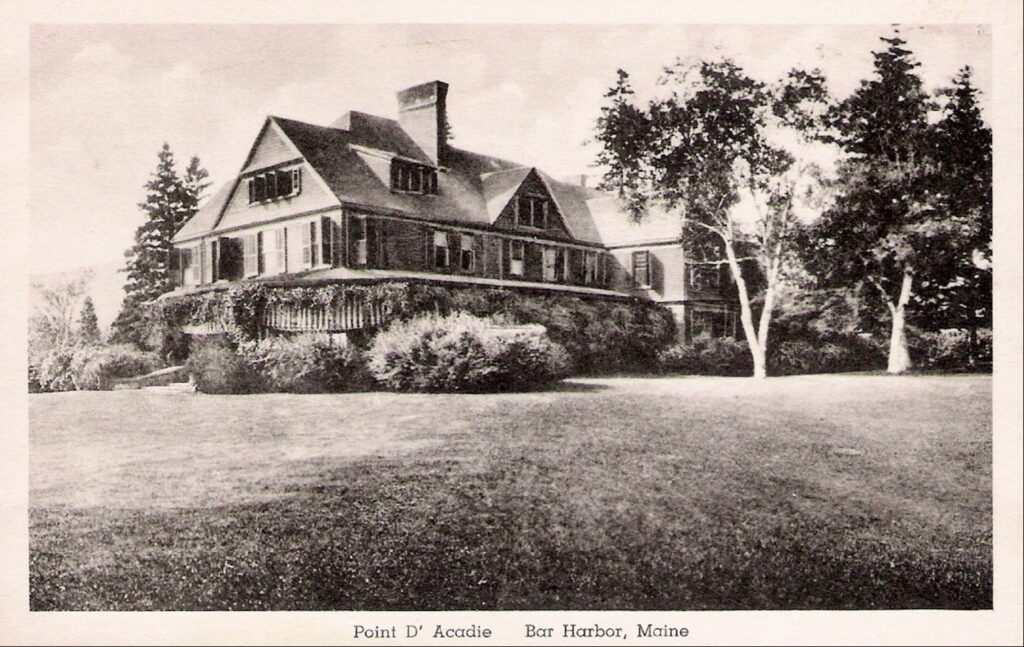

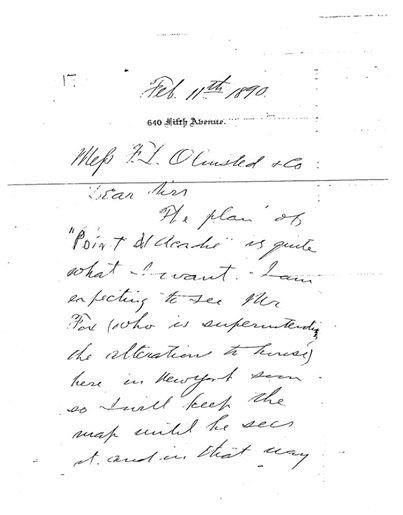

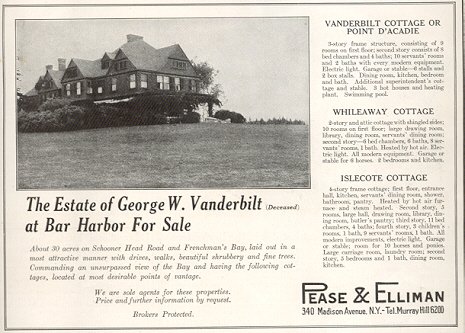

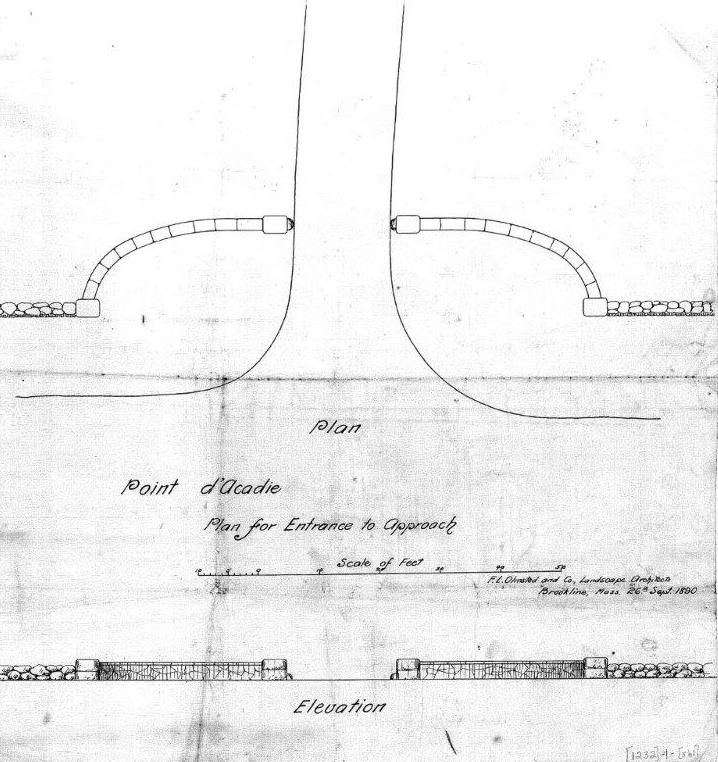

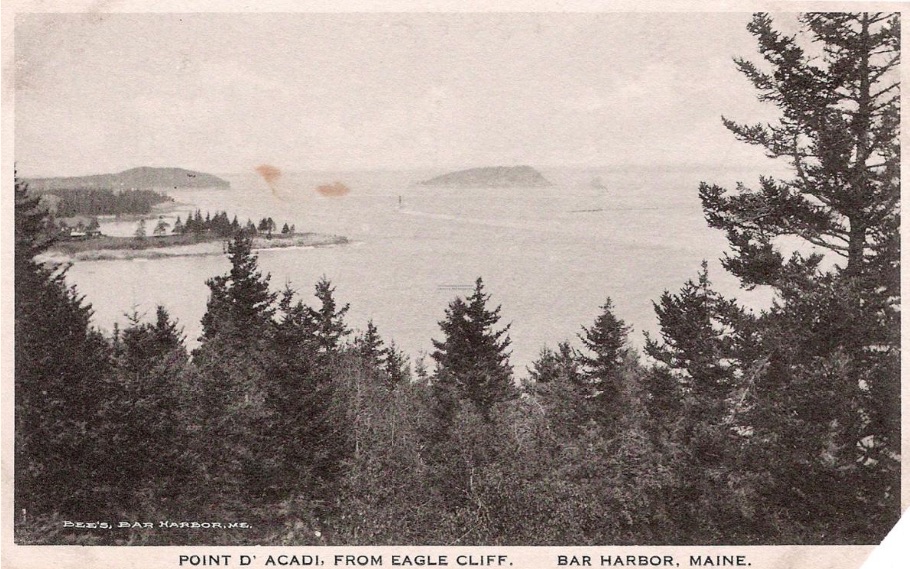

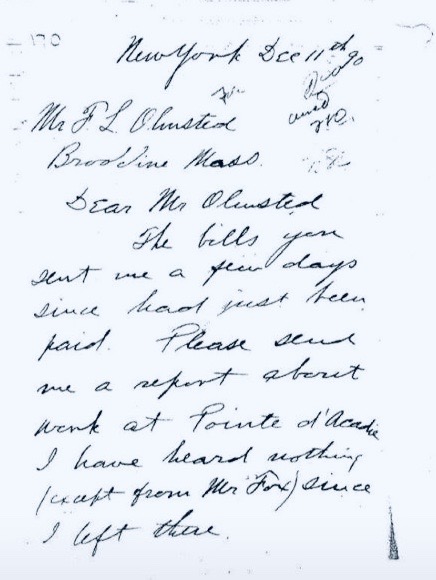

As someone who researches a wide variety of topics related to the intersection of art, architecture, and society during America’s Gilded Age, I have come across something that has confused and perplexed the small community of people who read, write, and think about such things. And that is whether the Bar Harbor “cottage” of George Washington Vanderbilt (1862–1914) was named Point d’Acadie or Pointe d’Acadie. Let’s establish at the outset that Vanderbilt himself, along with his landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, referred to the property as Point d’Acadie in letters and other documents (see examples below). But many other writers, historical organizations, bloggers, and researchers have variously used point, pointe, or both! I decided to spend a little time researching and thinking about this, and what you are reading today is a blog that has taken nearly three years to complete (with a few interruptions and sidetracks along the way).

STATUS OF FRENCH AMONG AMERICAN ELITES DURING THE GILDED AGE

During America’s Gilded Age, it was de rigeur for American elites to speak, read, and write French fluently. Home schooling of elite children by private tutors included the French language as one of the “required” subjects. Many elite children and teens of the Gilded Age, like George himself, traveled with their parents throughout Europe and spent long sojourns in Paris, then as now a city hugely popular with American travelers. George’s knowledge of French was excellent and he would have understood the difference in meaning between the two words, point and pointe.

Based on my analysis of the meanings and usages of the French words point and pointe in both Middle French and Modern French, along with period archival documents and published photographs, I conclude that Vanderbilt’s original name for his property in Maine was Point d’Acadie and that it is correctly spelled without “e”.

AS A LIBRARIAN ONCE TOLD ME: LOOK IT UP!

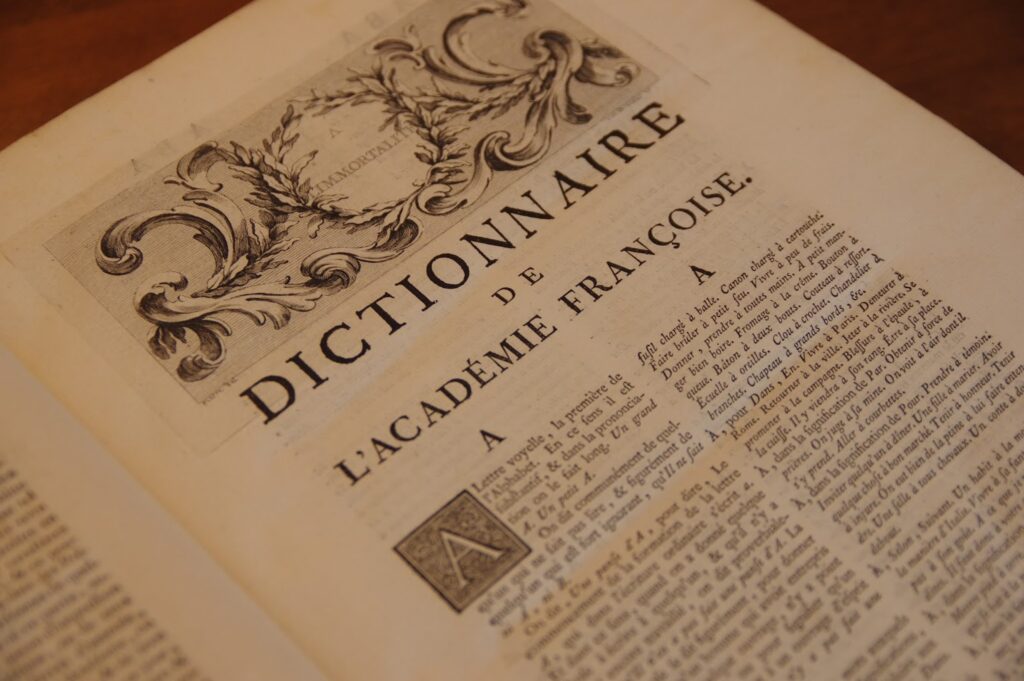

First, let’s look at the words themselves and their definitions, for they are each separate and distinct words in Modern French. The irrefutable source for analyzing the meaning and history of the words Point and Pointe is none other than the most authoritative source on the history and usage of the French language, the Academie Française in Paris, and its Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française.

In Middle French, the form of the language spoken and written from around 1330 to around 1500, the two words have different meanings:

- Point (masculine) is defined as “lieu donné, lieu précis” (a given area, a specific area).

- Pointe (feminine) is defined as “extrémité pointue ou objet pointu,” (pointed extremity or pointed object).

The definitions of point and pointe given in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française, 9th edition, show that these distinctive meanings have continued into Modern French. My summary of each of the Académie Française definitions (in bold) is followed by the complete definition in French as it appears in the dictionary of the French Academy.

Point (masculine) most often has a spatial or geographic sense including lookouts, panoramas, and belvederes.

Académie Française definition of Point: Le point culminant d’une chaîne de montagnes, où elle atteint sa plus haute altitude. Le point sublime d’une gorge, d’un canyon, qui, du fait de sa situation élevée, offre la vue la plus étendue. Point de vue, endroit à partir duquel on observe un paysage, une scène, belvédère ; lieu qui offre un panorama et, par méton., ce panorama lui-même.

[Sample usages:] Selon le point de vue que l’on adopte, cette place paraît ronde ou ovale. Ce beffroi est un bon point de vue pour découvrir la ville. Venez admirer le point de vue.

Pointe (feminine) most often has the sense of a pointed object, like a sword or a knife. Indeed, it appears frequently in military terminology to refer to weapons and other military devices with pointed tips and shapes. Pointe can also be used in specialized contexts to refer to the meaning or solution of an epigram, especially when this is naughty: the last word of the epigram that provides its solution is called the pointe. This is analogous to the English phrase “the point of the joke.”

Académie Française definition of Pointe: Extrémité piquante, aiguë d’un objet quelconque. Pointe acérée. La pointe d’une épine, d’une arête, d’une épée. Aiguiser, émousser la pointe d’un couteau. Les pointes d’un compas. Casque à pointe, orné à sa cime d’une pièce d’acier effilée, qui fut en usage dans l’armée prussienne puis allemande jusqu’à la Première Guerre mondiale.

[Sample usages :] Coup de pointe, attaque portée avec le bout du fleuret, de l’épée ou du sabre. À la pointe de l’épée, les armes à la main, de vive force et, fig., avec panache. Emporter un succès à la pointe de l’épée. Fig. Des pointes d’épingle, des détails infimes, des vétilles. • Fig. Trait d’esprit qui, à l’image de la flèche, touche au vif l’auditeur, soit pour le blesser, soit pour le délecter (on dit aussi Pique). Une pointe assassine. Ne parler que par pointes. Lancer, décocher des pointes brillantes. Spécialt. La pointe d’une épigramme, saillie, souvent méchante, réservée au dernier mot ou au dernier hémistiche de cette forme poétique. Art de la pointe, art de parler et d’écrire par pointes (agudeza, en espagnol ; acutezza, en italien), condamné par Boileau évoquant les « faux brillants du Tasse », qui a trouvé au XVIIe siècle hors de France, parmi les jésuites, de brillants théoriciens comme Baltasar Gracian et Emmanuele Tesauro. • Titre célèbre : La Pointe ou l’art du génie, de Baltasar Gracian (1648).

To put this all together succinctly (and in English!), the very different meanings of Point d’Acadie versus Pointe d’Acadie can be summarized as follows:

Point d’Acadie could be translated into English as: The Acadian View, The Acadian Panorama, Acadian Vista, or Acadian Belvedere, with core meanings that include such spatial concepts as wide view, outlook, and the actual process of seeing or looking.

Pointe d’Acadie could be translated as: The Acadian Arm or The Tip of Acadia, with core meanings that include such shapes as prong, tine, or spike in a static state that contrasts with the implied process state of viewing inherent in point.

Vanderbilt could have correctly chosen one or the other (but not both!) to name his property on Bar Harbor’s Ogden Point, but I believe he chose to focus the name on the magnificent and east-facing panorama seen from the property, not the shape of the land itself.

MODERN USE OF POINT D’ACADIE IN AMERICAN SCHOLARSHIP

There are many modern-day instances of the consistent use of Point d’Acadie in American scholarship on architectural history. For example:

Charles Capen McLaughlin and David Schuyer, et al., eds., The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: The Last Great Projects, 1890-1895, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015, uses the spelling Point d’Acadie in its critical apparatus, notes, and analysis.

John M. Bryan, Fred L. Savage and the Architecture of Mount Desert, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005, consistently uses the spelling Point d’Acadie.

Richard Walden Hale, 1949, The Story of Bar Harbor. New York, NY: Ives Washburn, 1949, consistently spells the name of the property as Point d’Acadie, for example, on page 167: “…the Vanderbilt house at Point d’Acadie, still a center of hospitality, but in other hands….”

And finally, the North Carolina Historical Review, which publishes frequently on George Vanderbilt, F.L. Olmsted, and Biltmore, uses Point d’Acadie, for example, in a recent article: Schuyler, David. “‘The Most Critical & the Most Difficult’ Project: Frederick Law Olmsted’s Biltmore.” The North Carolina Historical Review 92, no. 4 (2015): 361-86.

SO WHERE DID THE EXTRA “E” COME FROM?

The confusion between the presence or absence of “e” can be explained by a concept from linguistics. Linguists call such an addition of an extra letter or sound or other incorrect manipulation of a word or phrase, especially those of foreign origin, overcorrection (or sometimes hypercorrection). In this case, English speakers overcorrected the properly-used French word point to pointe because it looks “more French” than the correct form point. They did not make the change based on the history and vocabulary of the French language. One dictionary of linguistics defines this phenomenon as “The use of a nonstandard form due to a belief that it is more formal or more correct than the corresponding standard form.” Though both point and pointe are technically standard, the overwhelming preponderance of the evidence suggests that both Vanderbilt and Olmsted preferred point. The controversy comes from overcorrection.

When the American linguist Charles F. Hockett discussed “overcorrection” in his book A Course in Modern Linguistics, he specifically gave the example of overcorrection of French by speakers of English who themselves have no knoweldge of French. Hockett wrote: “Speakers of English who know no French get some value notion of the differences between French and English pronunciation, and may overcorrect,” in the case at hand, by adding the feminine ending –e because it sounds and looks “more French” than the “English-looking” point.

To be honest, Vanderbilt himself occasionally succumbed to the errant “e” overcorrection, as shown in the following letter to his landscape architect, F. L. Olmsted. But elsewhere he spelled it correctly (see above) showing that even a Vanderbilt who spoke elegant French could make the same mistake as many, many other Americans, past and present.

The author of this post holds a Ph.D. in Linguistics and French from Georgetown University. His training included courses in the history of the English and French languages, historical linguistics, and comparative linguistics. In 2016 he published the first full-length and dual biography of Larz and Isabel Anderson who were close friends of George Vanderbilt and his wife Edith Stuyvesant Dresser (1873–1958). He wishes to thank Ted Glasgow for generously sharing some of the images used in this post.