By Skip Moskey

In 1925, in response to a real estate development boom that was then spreading throughout the Boston suburbs in the wake of the nation’s burgeoning economy, Larz Anderson, who had served briefly as a U.S. Ambassador in 1913 and was one of the era’s most visible bon vivants, decided to try to increase the value of some unused land his wife Isabel Perkins Anderson owned near their estate in Brookline, Mass. Larz wrote in his diary that they built the houses to “keep up with the Joneses.” Indeed, only a spendthrift could build three extravagant houses that no one would ever live in.

These houses were among Larz’s most treasured pet projects. He had more than a passing knowledge of architecture, landscape design, and interior decoration, and had the circumstances of his life been otherwise, he would almost certainly have ended up one of the most celebrated Beaux-Arts architects of the early 20th century.

Larz enjoyed designing or commissioning many architectural projects over the course of his lifetime, including a small Japanese garden in Brookline, a classic Japanese pavilion at his wife’s rustic camp in New Hampshire, the Anderson Memorial Bridge in Boston, and even the St. Mary Chapel of the Washington National Cathedral, which he paid for and became very involved with, working directly with the architects and designers on the layout and decoration of the chapel. Thus, as he approached the development of new dwellings, much thought and planning went into their design and construction. “A small house requires almost more study than a large one,” Larz said, “and so there was a lot of talk and discussion about this little plan.”

The Andersons hired the Boston firm of Thomas A. Fox and Edwards J. Gale to design three small but perfectly-designed homes on Brookline’s Goddard Avenue, then a bucolic country lane that ran along the edge of the Anderson estate. The buildings were intended as souvenirs of some of their travels, recalling houses and construction materials that they found appealing.

The inspiration for the first of these, Blue Top (1925), was a house with a blue tile roof they had seen in Cadiz, Spain. Located at what is now 275 Goddard Avenue, the frame house had exterior walls of white stucco and a blue-glazed terra cotta tile roof.

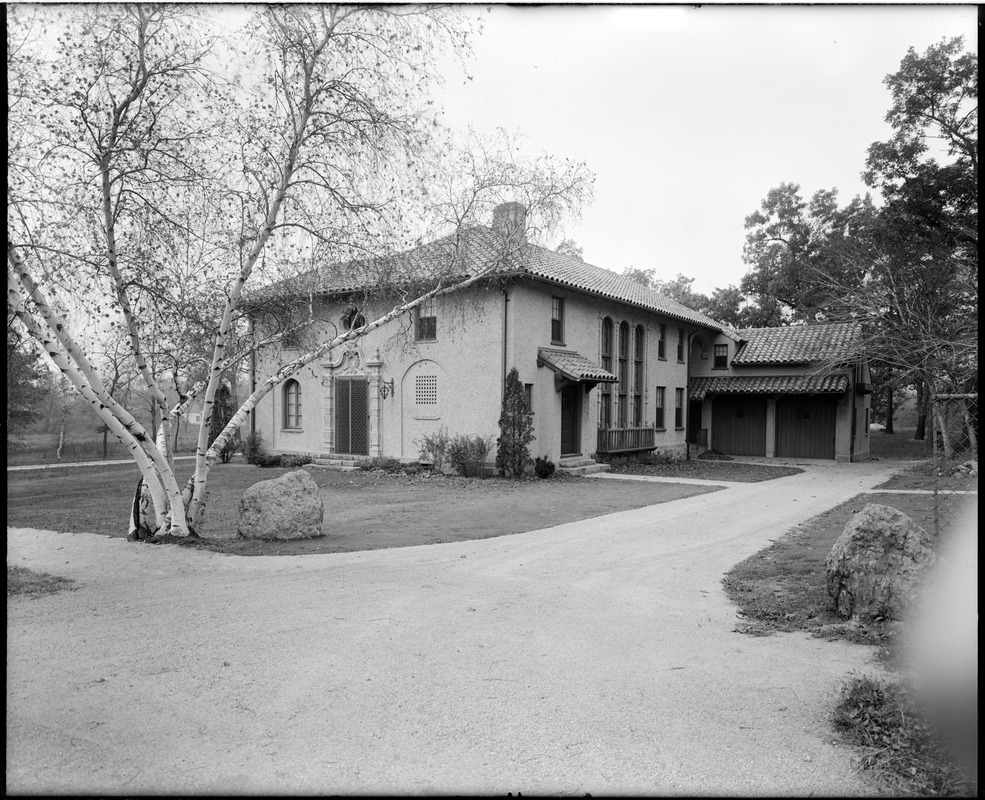

The second, Puddingstone (1927), was named for a nearby outcropping of puddingstone on the Anderson estate (see photo at the end of this blog), was modeled after one they had seen in Santa Monica, California. Built in a Spanish Colonial style, it also used red terra cotta roof tiles and adobe-colored stucco walls, but this house has a more decorative exterior. Its current house number is 325 Goddard Avenue.

The third house, Stellenbosch (1929), at 285 Goddard Avenue, was built in the Cape Dutch Colonial style found in South Africa, which the Andersons had visited the previous year. Of the three houses, this is my favorite.

After the houses were completed, Larz complained that the Town of Brookline would not allow the names he had given to the new structures to be used as their postal addresses. “The authorities require deadly numbers as an address,” he wrote in his journal, accepting the reality that the identity of his little architectural gems would be reduced to a number.

The Andersons used the buildings occasionally as guesthouses for relatives or friends who came for long stays at Weld, especially when Larz and Isabel were not in residence there. But for the most part, the houses remained empty and it was only after Larz’s death in 1937 that Isabel disposed of them. She donated them to Boston University for use as the Brookline Campus of what was then known as the College of Practical Arts and Letters, a two-year program that trained women for jobs as art teachers, medical secretaries, and similar fields. The university used them for this purpose for only a few years, and later sold the properties for use as private dwellings.

Text adapted from Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age, by Stephen T. Moskey, available on Amazon Prime. Copyright (c) 2016 by Stephen T. Moskey. All rights reserved.