by Skip Moskey

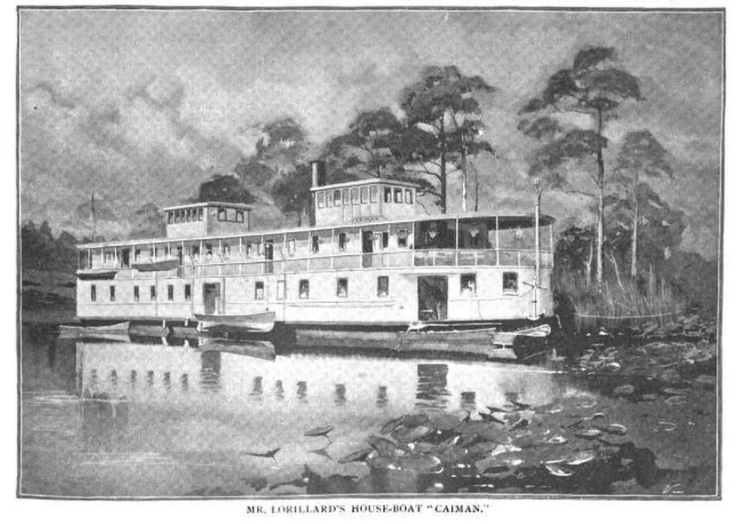

We often associate yachts and steamships with Gilded Age vacations and recreation, but did you know that houseboats were also once the “in” thing for wealthy boaters like Pierre Lorillard, Alfred Gwynn Vanderbilt, and William Payne Whitney? By the late 1890s, houseboating had become very popular both in the U.S. and in England, in part because the craft were easy to moor near shore or river’s edge, and served as the ultimate party boat. Reports of large parties aboard Lorillard’s craft the Caiman appeared regularly in society columns. Indeed, according to a New York Times article in August 1901, it was Lorillard’s Caiman that set the standard for “the luxurious life” aboard such watercraft. Larger craft such as Lorillard’s included as many as twelve to fifteen sleeping rooms, parlor, dining room, smoking room, and were often accompanied by a second boat that housed the kitchen and the staff.

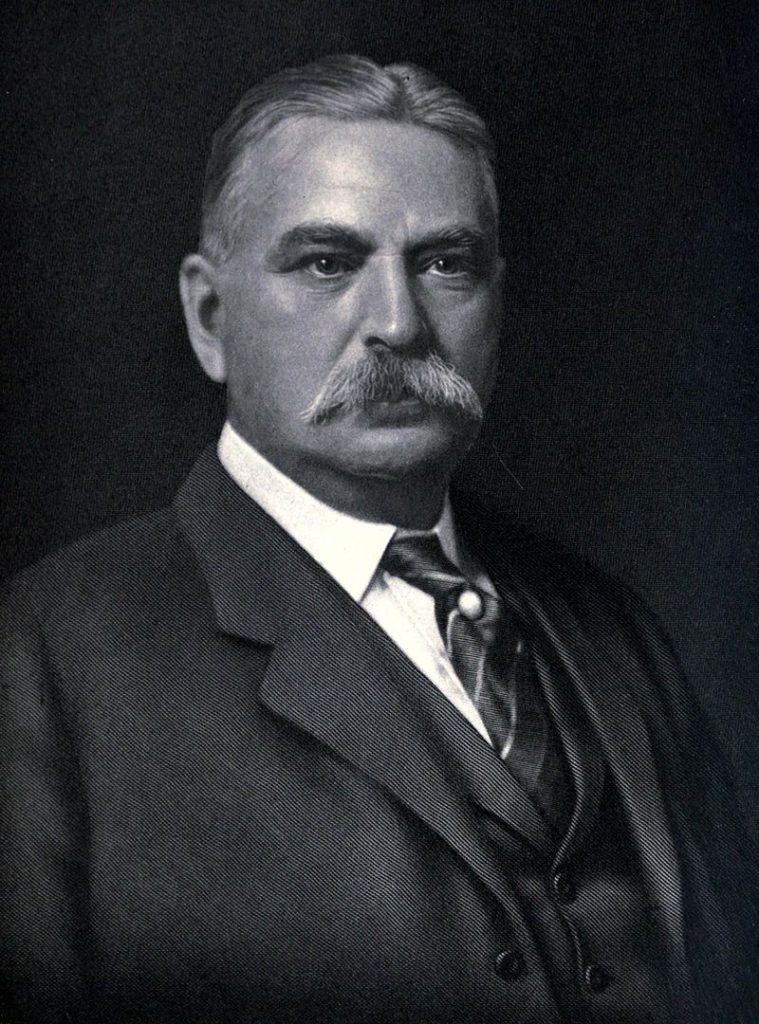

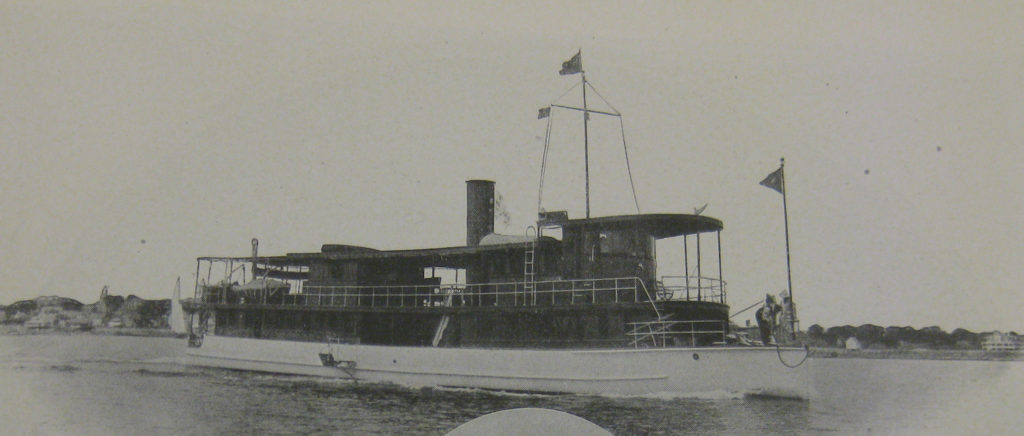

Millionaire John Warne “Bet-a-Million” Gates (1855–1911) was one of hundreds of men who commissioned a bespoke houseboat. Gates, a self-made man without much of an education, started out life as a barbed-wire salesman in Texas. He made plenty of money both in his business ventures and at casino tables. When he commissioned the Roxana from the Racine Boat Manufacturing Company, he wanted something of modest size. The vessel measured 112 feet long and 17 feet across and had a 4.5-foot draft. (In contrast, Lorillard’s Caiman was 132 feet long and 26 feet across and had a 5.5-foot draft.) Gates named his houseboat for Roxana, the wife of Alexander the Great, a fitting name for the pleasure craft of a king of industry.

Gates did not enjoy the Roxana for long. He spent two summers aboard the houseboat, in 1904 and 1905, and then appeared to grow tired of it. In 1906, he and his son, who were in business together, dissolved their New York City investment company in 1906, just ahead of the 1907 panic. They moved to Paris in 1907, where the elder Gates died four years later. His obituary noted he had been “adroit” in responding to stock market conditions, citing his decision to withdraw from the New York Stock Exchange at a time when the market was expanding rapidly.

When Larz Anderson first inspected the Roxana in early 1906 as a possible summer rental, it was boarded up at a marina in New York City. Gates agreed to lease the vessel to him with an option to buy it, which Larz did the following year. The Andersons frequently wintered aboard the Roxana, cruising lazily along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. They enjoyed everything connected to Florida waters, especially swimming and canoeing. One time they paddled their little boat around the coral islands near Caesar’s Creek in what is now Biscayne National Park. They marveled at the ocean bottom visible through the clear water and went diving for sponges. The couple loved to fish and did so often. Larz was thrilled to catch many varieties—herring, mackerel, red snapper, and grouper—and had their cook, a local whom he’d hired in Miami, prepare them for meals.

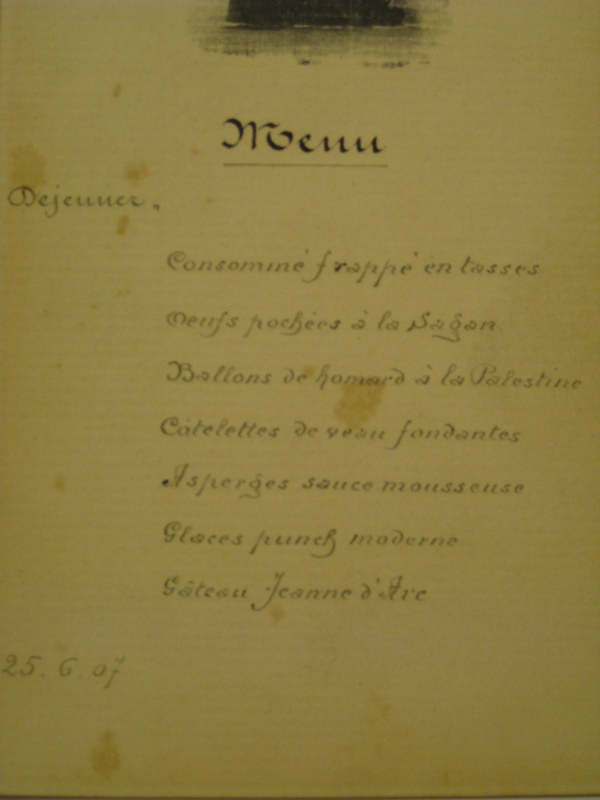

Like Lorillard and others, the Andersons entertained extensively aboard the Roxana. On June 25, 1907, when the boat was anchored near Annapolis, their cook served a mouthwatering luncheon that proved the galley’s catering standards equal to an Anderson kitchen on terra firma: frothy consommé, ramekin of poached egg with a cheese crust, buttered lobster in wine sauce, veal cutlets, asparagus with cream sauce, punch sorbet, and a cake named after Joan of Arc.

Larz and Isabel owned the Roxana for two decades, though they used it in only thirteen of those years. They did not use it in 1912 when Larz was US minister to Belgium, and they suspended cruising during the years US troops fought in World War I (1917–1918). Despite these breaks, the Andersons’ most regular use of the boat occurred before 1920. After 1920, the novelty of the houseboat had worn off, and eventually Larz came to prefer more-exotic itineraries than the Roxana could provide.

In 1927, Larz decided they would no longer use the Roxana, yet he found it difficult to let go of it. Larz “had a very strong sentiment about selling anything that he had enjoyed,” his business manager once said. Larz’s first impulse for disposing of the houseboat was “taking her out to sea and sinking her,” but Isabel objected. (After all, it had been her money that paid for the boat.) Larz eventually gave the Roxana to Captain Isaac Golden, who lived in Rhode Island, and kept him on the Anderson payroll for the rest of his life so that he could care for the vessel.

When Larz later wrote the history of how ownership of the houseboat had passed to Golden, he omitted the part about wanting to sink it.

Postscript: The fate of the Roxana after Captain Golden’s death in 1942 is unknown. Extensive searches and inquiries with nautical history organization in Rhode Island; attempts to locate Golden’s descendants, if any; and searches of newspaper records have not turned up even one clue. If you have a suggestion for how the Roxana’s fate might be determined, please let me know

Full technical information about the Roxana follows:

Official No.: 200436

Signal Letters: KSRM

Rig. St. s.

Decks 1

Masts 1

Gross tonnage. 132

Net tonnage. 74

Length. 112.2 (feet)

Breadth. 17.0 (feet)

Depth. 4.5

When built. 1903

Where built. Racine, Wis.

For much more information about Larz and Isabel Anderson, and life in the Gilded Age generally, please click here.