By Skip Moskey

Did you know that, like people, buildings have their own “genealogy”? I’m not talking about the style of a house (such as Gothic Revival, Art Deco, or International), nor am I talking about who has owned the house over time, though both of those things are important to fully understanding and appreciating the historical context of a building.

When I talk about the genealogy of a building, I’m interested in what its architectural antecedents were: what historical edifices might have served as models or ideas for the architect, or what historic homes might have inspired the owner to build a house of a particular style with particular features? Indeed, that was a question I asked myself almost ten years ago when I first visited a prominent historic house in Washington, DC — and ultimately became the biographer of both the house and its occupants.

The building I visited a decade ago is the Isabel and Larz Anderson House (known locally in Washington as Anderson House), built between 1902 and 1905 as the winter “party palace” of Boston author and philanthropist Isabel Weld Perkins Anderson (1876-1948), and her socialite husband Larz Kilgour Anderson (1866-1937). The construction cost of the mansion in 1905 was $750,000 (approximately $20 million today), with another $100,000 ($2.5 million) being spent on interior decoration and furnishings. The money to fund this construction project came entirely from Isabel’s trust fund of approximately $5.5 million ($141 million) which suggests that “The Isabel Anderson House” would be a more appropriate moniker for the residence. But I digress…

The question of which historical antecedents inspired Larz Anderson and his architects has been complicated by confusion in the literature on the actual architectural style of the house. When the house was completed in 1905, the Washington Post reported its architectural style as Florentine Villa, a mistake that continued well into the 20th century, when the 1994 (third) edition of The AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. labeled it an Italianate Palace. The AIA later changed their classification to neo-English Baroque [=early English Baroque] in its 2012 (5th) edition of the AIA Guide, an ornate style of architecture that is definitely not applicable to Anderson House. This error by the AIA is remarkable, because architectural historians Pamela Scott and Antoinette Lee had gotten it right almost two decades earlier in their 1993 encyclopedic survey Buildings of the District of Columbia, where they correctly classified Anderson House as English late Baroque.

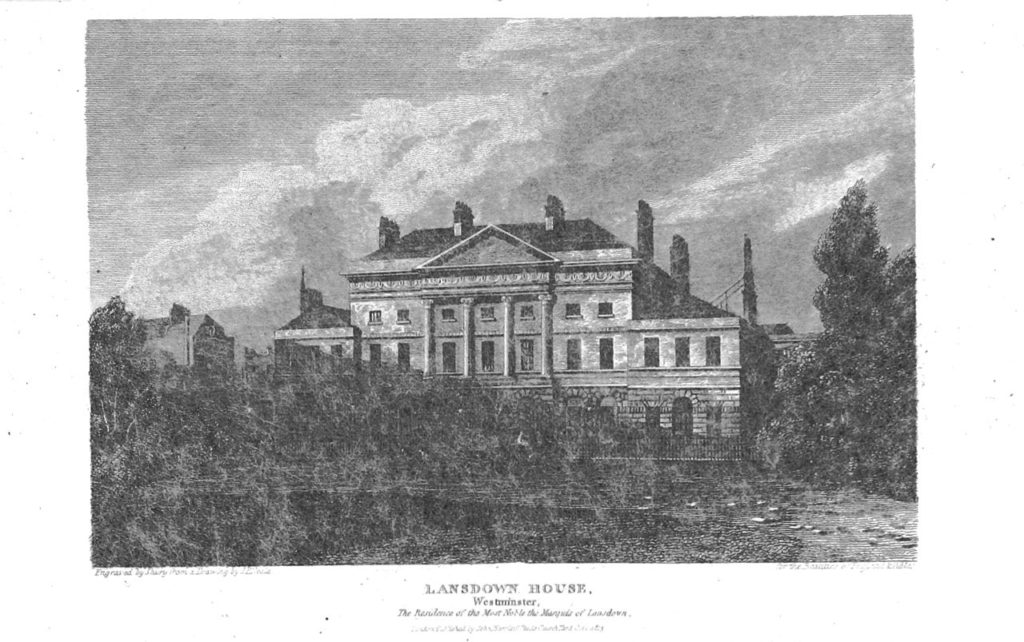

Around 1900 or 1901, when Larz Anderson started a conversation with the Boston architects Arthur Little and Herbert Browne about building a house in Washington, he almost certainly had London’s Lansdowne House in mind as an inspiration for the winter residence he wanted to build in the nation’s capital. The London townhouse was built in 1765 according to designs by Robert Adam, and Larz knew it well. He had visited it often a decade earlier, during the years that he was a junior diplomat at the American legation in London in the 1890s. Lansdowne House was the London town home of Mr. and Mrs. William Waldorf Astor during the time that Mr. Astor lived in self-imposed exile in England after a run-in with THE Mrs. Astor over who should be the “official” Mrs. Astor in New York. (His aunt, Mrs. William Backhouse Astor, Jr. (née Schermerhorn), won the battle.)

Lansdowne’s exterior and interior design, and its connection to one of the most powerful American families of the 19th century, the Astors, clearly made an impression on the young American diplomat, who had dreams of his own future greatness as an American ambassador. (The story of Larz’s checkered career in American diplomacy is told for the first time in Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age.) In his diaries, Larz recorded his visits with the Astors at Lansdowne House, during a period of his life when he was making frequent visits to other great houses of London and the English countryside. Since those other homes go largely un-mentioned in his diaries, it’s clear that for Larz, Lansdowne House had a particular appeal, perhaps as much for its “American royalty” occupants as for the architecture of the house itself. [1]

When one compares Anderson and Lansdowne houses, there are many similarities in massing and arrangement of structural and decorative elements, including an impressive pediment, pilasters, hipped roofs, and even the placement of chimneys. But the subsidiary wings of Lansdowne (seen more clearly in the illustration above) are not articulated forward as they are in Anderson House. There are, however, many examples of such articulation in other English houses; for example, Clarendon House in London (1664-1667) and Belton House in Lincolnshire (1685).

Though Larz had extensive exposure to English architecture and landscape design as a consequence of his long residence in England during his years as a diplomat there, he had an even more significant exposure to French and Italian culture. Larz’s almost accidental birth in Paris in 1866 during his parents’ 18-month wedding trip was the source of his life-long interest in all things French, though (unlike Isabel) he was not particularly fluent in the language. [2] Though a late English Baroque style of country home provided Larz with the size and stature that he wanted for his in-town residence in Washington, it’s almost certain that he looked to Paris for decorative touches that would reflect his “French connection.”

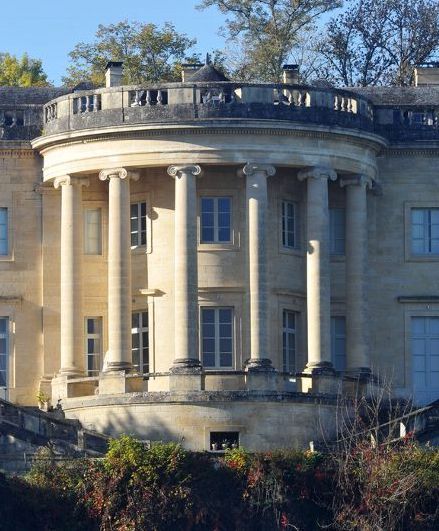

There are several important architectural elements of Anderson House that were inspired by Parisian townhomes. To understand this more clearly, start by comparing the Greg Tinius photo of Anderson House with the photo of Belton House just above it. All of the significant differences between Belton and Anderson houses can be traced to French antecedents: the entryway, pediment, and portico (See below). Indeed, it is the French influence on Anderson House that ultimately creates a truly artistic effect and gives the house a unique architectural personality. Were it not for these very French elements, Anderson House as a pure example of late English Baroque architecture (i.e., without French accents) might seem more pedestrian and more predictable. The French touches in the exterior of the house create texture and depth that would otherwise be missing from a purely-English structure such as Belton House.

If Anderson House were a person, I think it would be fair to say that though English is its native language, it speaks the language of Shakespeare with a slight Parisian accent and a vocabulary chosen from the language of Molière.

Gallery: French Influences on Anderson House

Entryway

Pediment

Portico

This essay was adapted from “A Tale of Two Houses: The Architecture and Interior Decoration of Washington’s Townsend and Anderson Residences,” a lecture that I and art historian Dr. Isabel Taube of New York City co-presented to the Cosmos Club Historical Preservation Foundation in Washington, DC, on November 12, 2018. Though the views and analysis presented here are my own, I want to acknowledge Dr. Taube’s important contribution to my thinking on these issues.

P

Notes

[1] In January 1892, Larz made the first of several visits to Hardwick House in Oxfordshire, the country home of the Anglo-Canadian businessman, racehorse breeder, yachtsman, and British Liberal Party politician, Sir Charles Day Rose (1847-1913). Author Kenneth Grahame used Sir Charles as the inspiration for the Wind in the Willows character, Mr. Toad, and set the story at Hardwick House.

[2] Larz’s knowledge of and appreciation for Italian art, architecture, and garden design far exceeded his interest in either English or French culture. Indeed, his deep appreciation of Italian culture was a theme throughout the course of his adult life, as documented in my full-length biography of the Andersons, Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age.