In Part 1 of this two-part series, I reviewed the relationship between the architectural form and intended social function of Washington, DC’s Anderson House, which from 1905 until around 1930 was the winter party palace of Larz and Isabel Anderson. It was a house that was planned, first, to make sure that all who saw or visited it understood that its owners were powerful people of good taste; and second, to entertain select individuals drawn from Washington’s elite society at teas, dinners, cocktail parties, and musical performance. The house was designed to move guests through an ever-changing interior “landscape” of spaces, rooms, views, and experiences that enhanced the social and gastronomic elements of an evening dinner party or late-night musicale. Now, Part 2 of this series on “The Genius of Anderson House” shows how that relationship between form and function played out at one particularly glamorous dinner party that the Andersons gave on Friday, May 30, 1917.

A Dinner Party for Italian Royalty

His Royal Highness The Prince of Udine was to be the guest of honor at this evening’s dinner party. A cousin of Italy’s reigning monarch, King Victor Emmanuel III, the prince was one of the most important visitors to the nation’s capital during the 1917 social season. World War I was raging in Europe and the presence of an Italian royal at the Andersons’ dinner table had both political and social import. Twenty years earlier Larz Anderson had served as first secretary at the American Embassy in Rome. He would have been very pleased indeed if any of his guests speculated idly among themselves that he was in some way involved in the conduct of the war – in a behind-the-scenes kind of way, of course.

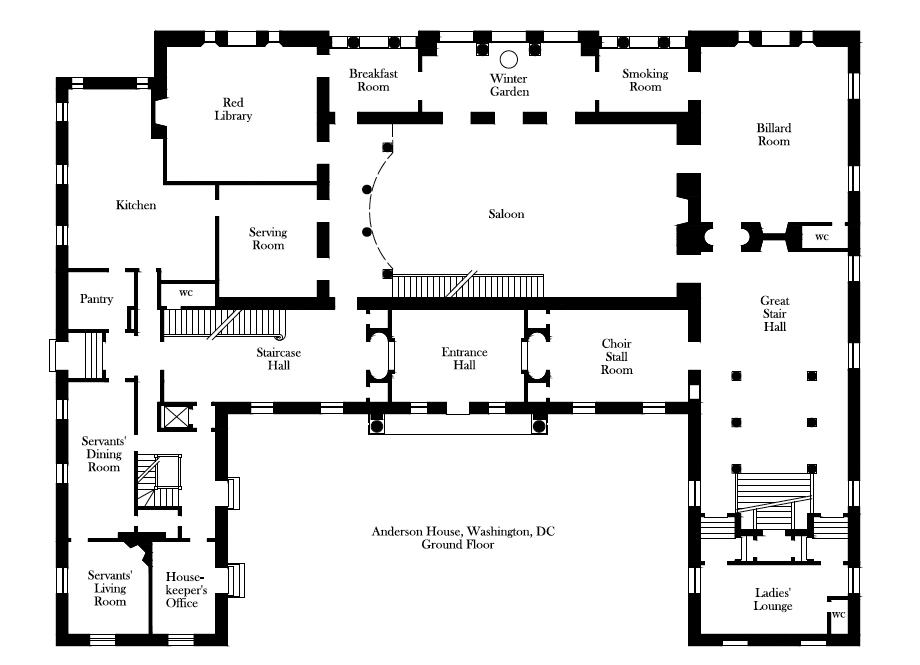

By 7:45 p.m., more than two-dozen servants stood ready to attend to the needs of the thirty very select guests who had been invited to what was without doubt the most important event of Washington’s winter social season that year, in the loveliest of Washington’s great houses. The guests would begin arriving as if on cue at 8:00 p.m., and the servants were tasked with getting the guests up to the second floor of the mansion as efficiently as possible. The hosts, the celebrity guests, and cocktails were waiting above!

One by one, elegant horse-drawn carriages pulled up to the mansion’s front door, situated in an elegant forecourt that provided protection from prying eyes on the sidewalk. As the guests alighted from their carriages, footmen helped them to the front door, where they were greeted by the Andersons’ butler. Larz and Isabel may have been host and hostess for this evening, but the Butler was in charge!

As guests arrived, they were ushered through the mansion’s broad paneled door into the Entrance Hall. There, they came face-to-face with a giant statue of the Buddha that was flanked by bronze Japanese temple lanterns. If you did not know anything about the Andersons before this moment, you now at least knew they had exotic “Oriental” interests and tastes.

The guests did not linger long in the entry way. They were immediately whisked away to the right through a room called The Choir Stall Room, with old Italian church paneling installed around the walls. But the choir stalls were not the highlight of the room. The visitors’ eyes were drawn from the dark sombre walnut panels below to the bright, colorful ceiling above, decorated with dozens of medallions, coats of arms, emblems, and cartouches. I always think of this as Larz’s “bragging room,” where he could show off the couple’s academic degrees, memberships in academic and patriotic organizations, awards, and decorations. Though the meaning of these medallions and cartouches might be a bit vague for modern visitors, in 1917 their significance would have been immediately apparent to anyone from Washington’s elite social class.

Once they passed through the Choir Stall Room, guests arrived in the Grand Staircase Hall, where maids would help the ladies with their coats, and footmen would help the gentlemen with their hats and walking sticks. The arched doorway in the far left corner led to a ladies lounge, and the one on the right, to a gentleman’s lounge one level below, under the grand hall. Once they were ready, guests were escorted up the grand staircase, to begin the evening’s festivities.

As guests ascended the grand stairway, they could contemplate the pomp and circumstance depicted in a billboard-sized painting in the stairway: The Triumph of the Dogaressa of Venice by Spanish artist Jose Villegas y Cordero. It is said that Larz felt that this painting would set the mood for an event that his guests would soon experience on the piano nobile, or “noble floor,” of Anderson House.

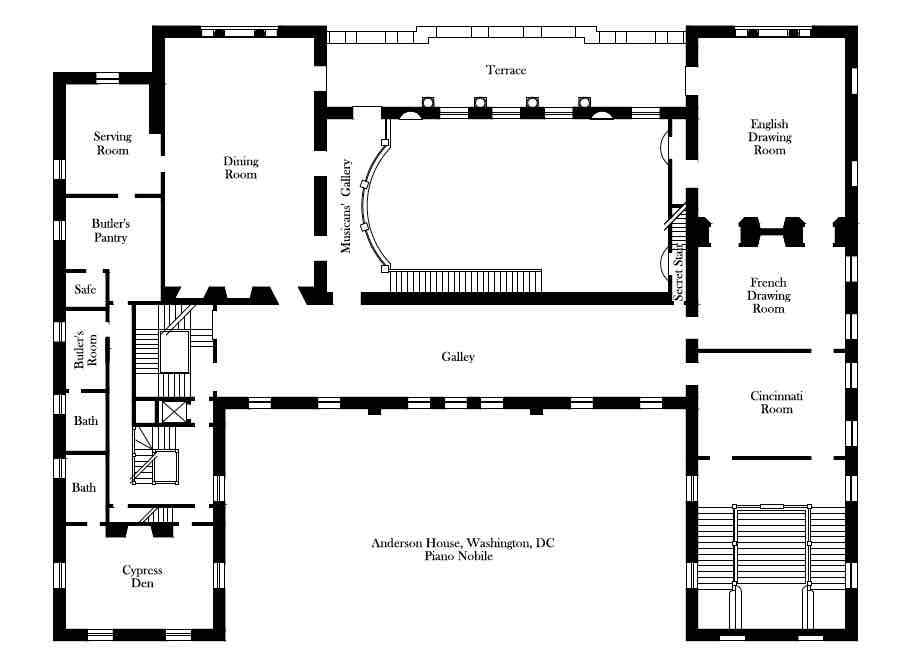

At the top of the stairs, guests entered a reception area the Andersons sometimes called the Cincinnati Room, a reference to the murals depicting both the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati and the early history of the city of Cincinnati. (The Andersons also sometimes called it the Key Room, as it is now known—a reference to the meander, or Greek key, design of the marble floor.) This was the anteroom to the rest of the piano nobile.

The Andersons, the prince, and the count and countess greeted each guest as they were announced at the top of the staircase. Introductions and brief polite conversation ensued, but only briefly. There were many guests to be processed through these arrival rituals, and cocktails were waiting!

After passing through the Cincinnati Room, guests gathered in two adjoining drawing rooms, one in French style and one in English style. Cocktails and conversation were the order of the evening in these two elegant rooms. Once everyone had arrived, Larz and Isabel and their honored guests joined the others in these rooms. The Andersons were delightful hosts who mingled with their guests and made sure everyone had a cocktail.

Around nine o’clock, after a few rounds of cocktails, guests assembled in order of social precedence that Isabel had carefully spelled out in a “dinner chart” she created for the dinner. Using the chart as his guide, the butler paired each gentleman with a lady for the procession down the long gallery that led to the dining room on the other side of the house. The gallery, filled chockablock with mementos of Anderson travels, gave silent testimony to the magnificence of the hosts’ lives.

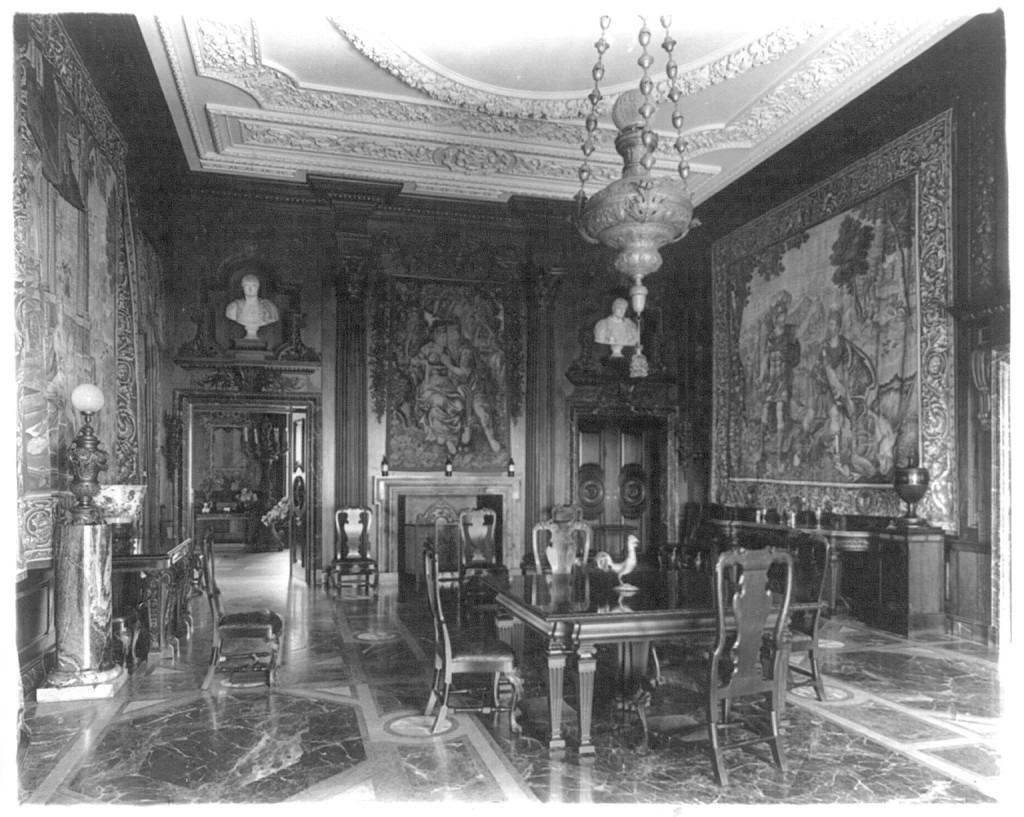

The french-walnut-paneled dining room, adorned with priceless Belgian tapestries commissioned by the French King Louis VIII as a gift to the pope’s emissary, Cardinal Barberini, was a cosy and elegant setting for the dinner. Isabel believed in giving “modern” dinner parties with fewer than 15 couples, and often only 10 or 11. (In contrast, dinner parties in the late 19th century, were given for as many as 100 or more people!)

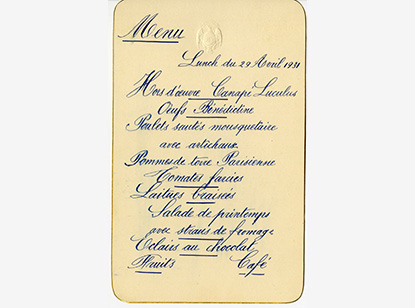

Unfortunately, there are very few examples of Anderson menus. The guest lists and seating charts were saved, but not a record of what was served.

After dinner, the guests descended the mansion’s famous “floating staircase” into the vast room below that had been designed for entertainment and relaxation. Many more guests had been invited to arrive after dinner to meet the prince and his entourage. Coffee, cigarettes, and cordials added to the late evening’s conviviality. Isabel’s choice of performers and programs at her after-dinner entertainments favored European musical traditions. One evening, Mademoiselle Germaine Arnaud, a French-born British pianist and vocalist, accompanied by the Irish pianist, composer, and conductor Sir Hamilton Harty, sang a selection of pieces by Bach, Chopin, and Saint-Saëns. On another evening, Miss Marie Hall, an internationally acclaimed English violinist, performed a program of Polish, French, and Italian music.

The next morning, the Washington Post called the Anderson dinner party for the Italian VIPs “a particularly interesting function” because of Larz’s diplomatic past. Larz’s publicist made sure the reporter did not forget other details of his biography. The brief article reminded readers that Larz had married into Boston wealth, had been part of the Taft administration, and had been decorated by the Italian king.

Anderson parties always made good copy.

To learn more about Larz and Isabel Anderson and their fascinating Gilded Age lifestyle, please read Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age by Stephen T. Moskey, available on Amazon Prime and from your local bookseller.

Portions of this blog are excerpted from Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age by Stephen T. Moskey (iUniverse 2016). This blog and its content are Copyright (c) 2016-2018 by Stephen T. Moskey. All rights reserved.