By Skip Moskey

Anderson House in Washington, D.C., the winter home of Larz and Isabel Anderson from 1905 until 1937, was designed by the Boston firm of Little and Browne with two purposes in mind: first, to make a statement about the importance of the mansion’s owners; and second, to provide a series of elegant public rooms and spaces that were arranged to encourage convivial events that included cocktails, food, musical entertainment, genteel conversation, and an opportunity for Washington’s power brokers to meet and greet.

Anderson House truly is a case of “form follows function.” In his journals, Larz wrote in great detail about all of the decisions that he and his architects had to make about such details as the placement of the grand staircase or if the winter garden should be one story or two. Each decision about the form of the house was informed by, and satisfied, the needs defined by its function.

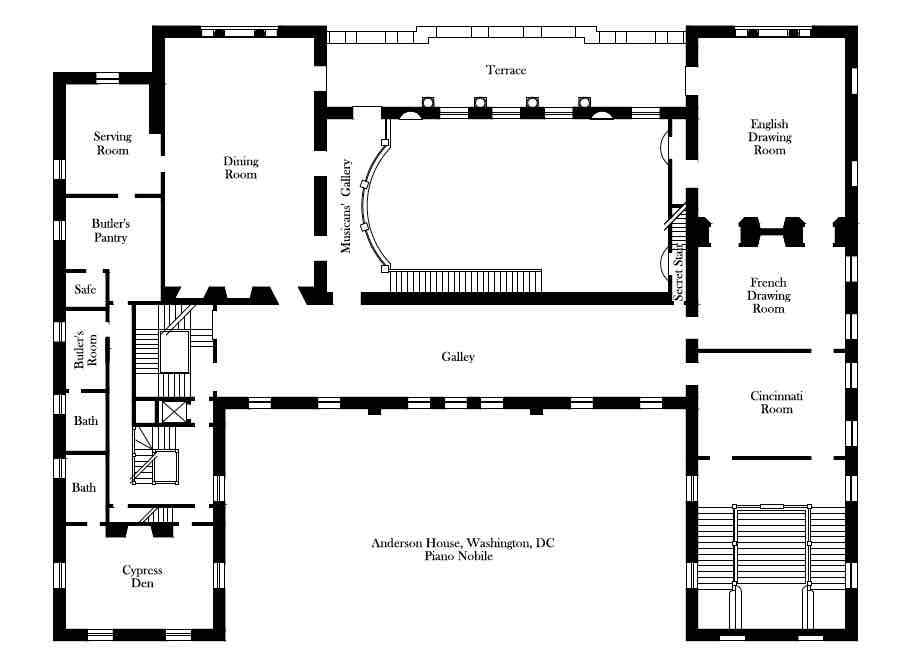

The plan of the ground floor and piano nobile of Anderson House provided a route along which a dinner party could steadily progress over the course of an evening. Arrival, greeting, cocktailing, dining, and after-dinner entertainment occurred in a series of discrete rooms arranged in sequential order, from arrival to departure. Guests moved continuously through spaces they had not seen previously, each room presenting a new experience of design, perspectives, lighting, and objects. Once the progression started, there was no backtracking. Each phase of a dinner party occurred in a new space or room.

Upon their arrival, guests would give their coats to the house staff in a grand hallway, and then proceed up a grand stairway that was dominated by a magnificent work of art, Triumph of the Dogaressa of Venice by Spanish artist Jose y Cordero Villegas. Before they had even reached the main floor of the house, the guests had a clue of what awaited them.

At the top of the stairs, the guests entered the Cincinnati Room, where Larz and Isabel, along with their guests of honor, received their guests. The room, the most magnificently decorated and imposing space of Anderson House, was richly decorated with painted murals that told the story of the Anderson family’s place in American history. Guests could have no doubt that their host was from a family that had provided glorious military service to the nation.

Once the guests went through the receiving line, they entered the French and English drawing rooms to mix and mingle before dinner. The drawing rooms were never too crowded or too empty. They were scaled perfectly to a typical Anderson guest list of no more than thirty people.

When it was time to go in to dinner, the Chief Butler would organize the guests for their processing down a long gallery that connected the drawing rooms to the dining room. It was here the Andersons exhibited the most important objects from their collections, especially the Flemish tapestries. The guests would marvel at the wonderful, eclectic objects d’art that meant so much to the Andersons.

And then, at the end of their long procession down the gallery, the guests arrived at their destination: the French-walnut-paneled dining room that displayed its own collection of rare tapestries and imperial Japanese porcelains.

By the time Anderson House was built, the preference in Washington had shifted from the post–Civil War period’s large dinners with thirty or more couples and balls for hundreds to the “modern dinner-party which has come to be the favorite form of entertainment … of especial significance at the capital,” wrote etiquette expert Florence Howe Hall. Such dinner parties gave “an opportunity for conversation.”

Isabel Anderson took note of this trend as well as differences between the social dynamics of American and European dinner parties when she wrote:

In America, at a dinner party, one talked with her immediate neighbors, and if one is fortunate enough to sit beside a general or a diplomat or a distinguished statesman, or a minister, he will talk more freely and more interestingly to one person. Now in Europe, the conversation is general, and one person will seize the opportunity for monologue.

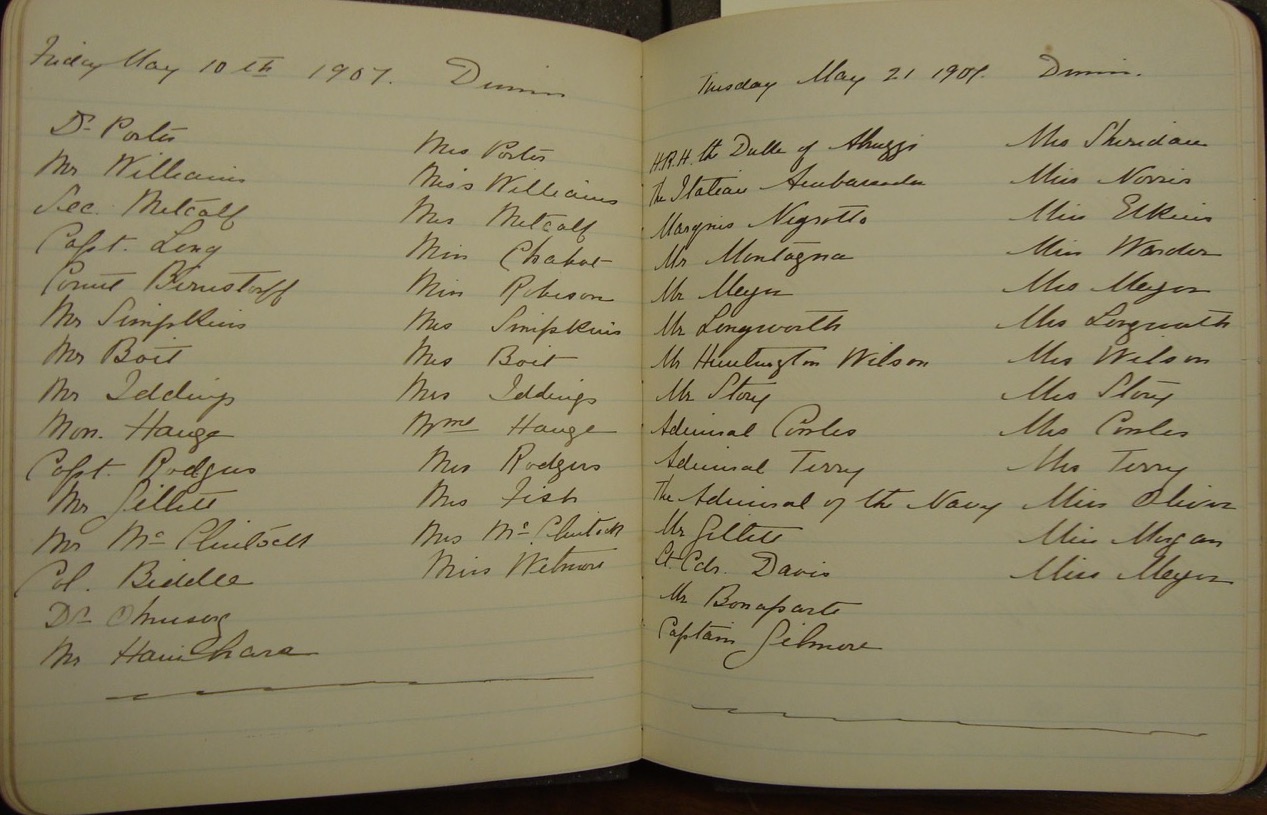

Each Anderson dinner party, carefully recorded in Isabel Anderson’s “dinner books”, party rarely exceeded more than 12–14 couples.

Coming Soon: After-Dinner Entertainment at Anderson House.

Click here to order a copy of the biography this amazing couple!

This blog post is based on an excerpt from my book, Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age, slightly adapted to the blog's format, and with the addition of photographs. Copyright © 2016–2017 by Stephen T. Moskey.